But in another lifetime, more than 30 years ago, during the Vietnam war, he was known as Mr. Jones, Warrant Officer, pilot of helicopters. (According to Mike Guard, Jones' Crew Chief in Vietnam, Jones was "The World's Best Gunship Pilot!")

In 1969, Jones was flying "hunter-killer" missions in the Mekong Delta, in a UH-1 (Huey) gunship. This ship was affectionately referred to as a "hog," meaning the helicopter carried a C2 rocket pod (consisting of 38, 2.75" rockets) and a freehand M-60 gun, on either side of the plane.

Mike Guard remembers one of those missions. Jones' helicopter was called away from a rather routine mission to answer a distress call from an ARVN (South Vietnamese) artillery outpost south of Vung Tau, which was being overrun by a battalion of North Vietnamese regulars.

Two of Jones' support helicopters dropped flares around the wooded area from which the enemy fire was coming.

The North Vietnamese were firing what seemed to be automatic mortar fire.

Jones began the attack, which proceeded smoothly as long as the flares lasted. When the flares burned out the only means of identifying the enemy position was by the flashes coming from the mortars.

(Note: In firing the rockets from a Huey Warship, one aims his fire by literally aiming the helicopter -- the closer the plane is to the target the steeper the attitude of the aircraft must be. This makes flying near trees very tricky. With no lights, one must depend entirely on the helicopter's altimeter to keep a safe distance from the ground and from the trees.)

Mike Guard remembers hearing Jones formulating his attack with his co-pilot and his support helicopters.

While the support planes dropped parachute flares, Jones would attack from a strike altitude of 2,000 feet and break out at 500 feet.

His instructions to the co-pilot, "Keep your eye on the altimeter, call out 500 feet and I'll break right."

Unfortunately, Jones' co-pilot was a new arrival to Vietnam. He had never flown a "hunter-killer" mission and he had no nighttime combat experience.

As Jones aimed his helicopter into the darkness from strike altitude, his crew opened up with M-60 guns from both sides of the aircraft. Guard says,

"Our red tracers spewed out like a laser light show and the rockets, two at a time, were white hot streams of sparks leading to the target as fast as Jones could fire."

Guard continues, "Well, the co-pilot must have thought it was the Fourth of July and never thought to look at the altimeter -- all the way to the trees."

At the last moment Jones sensed that they were too low and attempted to gain altitude. It was too late. As the helicopter made contact with the trees there was a loud explosion.

Mike Guard was halfway out of the aircraft, firing his M-60 forward. He could not see anything beyond the muzzle flashes of his gun. Then, suddenly, he was just hanging upside down by his loose seat belt, like a rag doll.

As he tried to get back into his jump seat the aircraft hit more trees, with bone-jarring force.

In the darkness it seemed to Mike Guard that they were rolling along on very rough ground. He heard sounds coming from that Huey that he'd never heard before -- loud whistling sounds, and the wind, coming through the front of the plane, roared directly into his face. The vibration of the airship was the worst he had ever experienced.

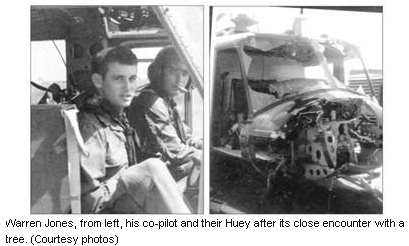

A tree limb had exploded through the floor panels. The windshield, the greenhouse over the co-pilot, both chin bubbles, the complete avionic section of the nose, and probably three feet of both rotor blades (the source of the whistling), were all gone.

Plexiglas particles had entered the eyes of the co-pilot, and that, coupled with a 100 mph blast of air, had blinded him so that he was unable to handle the controls on his side of the copter. The left and right seat gunners were bruised and shaken.

Fortunately, Jones was only slightly hurt and was still in control of the helicopter -- barely.

"He had only one rotor pedal left; the other dangled uselessly below the plane. But by using one foot in front of that remaining rotor pedal and one behind, he was able to move fore and aft. But he had no aft cyclic, which meant that any landing would be made at 70-90 knots.

(Ordinarily helicopters make their landing by hovering over the landing site and gently descending straight down to a smooth landing on skids, not wheels. Landing at 70-90 knots would be extremely dangerous.)

Mike Guard, as chief of the mechanical functions of the plane, insisted that they land at once on an open rice paddy. He wanted to be on the ground immediately.

Warrant Officer Jones would have no part of such a plan, since they were still in contact with the enemy and landing would mean certain capture. Jones was confident that he could still fly the aircraft, using both feet to operate the one foot pedal, and varying the throttle to somewhat offset the loss of the aft cyclic. He was sure they could land at Vung Tai, the nearest friendly field.

Jones' wing-ships had seen what had happened. They alerted the field at Vung Tai, and proceeded to accompany the stricken aircraft back to safety. As they approached the field the crew could see crash vehicles lined up on either side of the runway, awaiting the impending crash. Airmen from the base were on hand to witness the event. Jones touched down at 70 knots and immediately rolled off the throttle. Sparks flew and Guard could feel the heat from the skids as they ground down. After some 200 yards, in what seemed like the longest slide in history, the aircraft began a skid sideways, at 45 degrees to the runway.

Guard was immediately on the ground, to help Jones from the plane. There was no need to help the co-pilot. The exterior of the plane, in front of him, had been torn away by the tree branches. All he had to do was unbuckle his safety belt and slide out straight ahead.

Jones ordered the members of his crew to report to the base hospital for examination, including the co-pilot, who was carried away on a stretcher. Jones remained in the helicopter while he completed the entry in his log book.

He was accosted by a senior officer who demanded to know 1. Where Jones' men were? and 2. Why in the world Jones was not at the hospital getting checked out himself?

A day later Warrant Officer Jones was on hand when his Huey helicopter was loaded on a flatbed truck and hauled away, presumably to the junk pile.

Mike Guard concluded his story, "WO Jones, thanks man! You truly saved our lives that night. I did not think it possible to fly that machine in that condition … I want you to know, and anyone else who reads this, you are the best pilot! God Bless You."

When Warren Jones was asked about Mike Guard's account of the miraculous flight, and especially about his reaction to Mike's tribute, he merely smiled and said, "I'll tell you just like I told Mike when I talked to him on the phone. I knew I was either going to get a medal or get court marshaled for destroying that helicopter.

"I was merely doing my job, just like we all were. As for saving Mike's life and the lives of the crewmen -- he's got it backwards. I was the fellow who got them into that situation. It never should have happened. The least I could do was to try to get us all out of it as best I could."

And the helicopter? -- Just recently, after some 37 years, Warren has learned that his Huey aircraft was not relegated to the junk pile as he had supposed.

It was not only salvaged -- it was sent back to the United States, refurbished with a larger engine, and put back into service with a National Guard Unit. Jones and his crew have a soft spot in their hearts for that dependable aircraft that defied the odds and got them all back safely.

Source: "Warrant Officer Pilot Saved Lives Of Crew", by Michael Guard, in the VHPA Newsletter, July/August 1997